Ancient historic sites have long been a staple of Egyptian tourism. With the Grand Pyramids of Giza, more than 120,000 artifacts in the Museum of Egyptian Antiquities and several temples in Luxor and Aswan, it was perhaps only natural. Atef Abdullatif, president of the Travelers Association for Tourism and Travel, told Egypt Independent in 2017 that “visiting Luxor and Aswan is a dream for many foreign tourists.”

That year, CAPMAS reported that 8.36 million foreign tourists visited Egypt. That figure includes those who spent their time at seaside resorts, such as Sharm El Sheikh and Hurghada, as well as historical sites, such as temples and pyramids. The government doesn’t have a breakdown of who visited which parts of the country. However, according to online independent travel guide Addison Lee and Giza Pyramid Tickets, over 14 million people visited the Pyramids in 2017. That figure likely includes domestic visitors and repeat visits during a single trip.

That momentum carried on to 2018. Abdullatif says hotels in Luxor saw between 80% and 90% occupancy rates during the end-of-year holiday season.

With the travel restrictions and lockdowns of the COVID-19 pandemic, the tourism revenue in Egypt hit. Revenues fell 70%, from $13 billion to $3.5 to $4 billion in the first half of 2020, Ghada Shalaby, deputy minister of tourism, told Reuters at the time. By 2021, tourism looked to be back on track with $13 billion in revenue, according to the Ministry of Tourism. By FY 2021/2022, the CBE recorded that tourism revenues had reached $8.2 billion.

The opening of the National Museum of Egyptian Civilization in 2021 boosted the tourism sector. In May 2021, the museum, which houses 22 royal mummies, reported 12,000 visitors over one weekend.

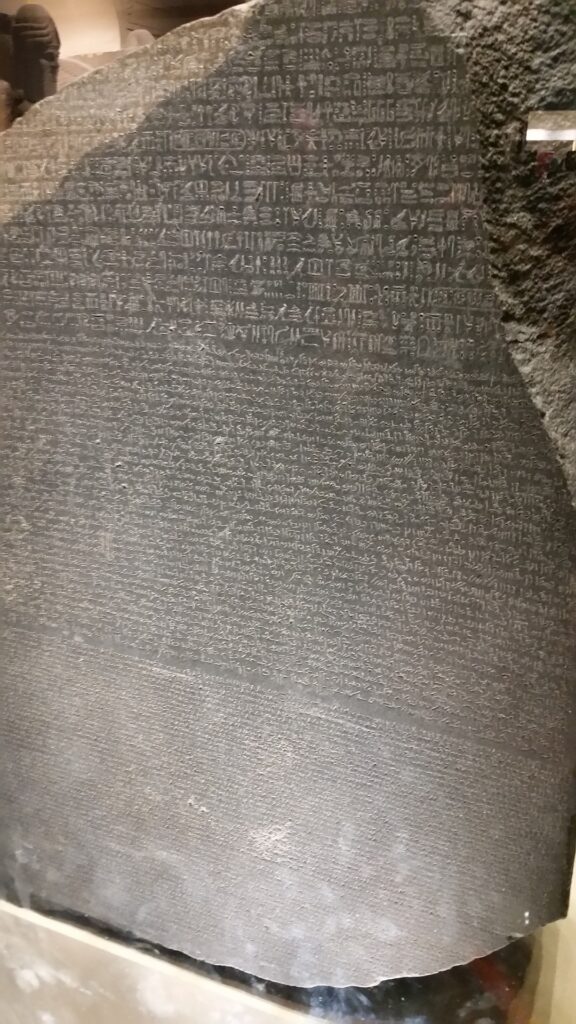

Now, the anticipated opening of the Grand Egyptian Museum (GEM) in 2023 has renewed calls for the repatriation of Egyptian artifacts on display at European museums. A significant voice is that of former Minister of State for Antiquities Affairs Zahi Hawass, who started a petition on change.org calling for the return of the Rosetta Stone and Dendera Zodiac. As of press time, the petition was signed by over 143 thousand people.

“Borrowed” history

Hawass launched the petition to “make sure museums stop the unethical practice of purchasing stolen objects.” When Egypt was under French and then British control in the 18th and 19th centuries, he explained, “the country was plundered, and many of its antiquities were illegally exported.”

The Rosetta Stone, whose inscriptions were the key to deciphering Pharaonic hieroglyphs, was found in the city of Rosetta (now called Rashid), east of Alexandria, in 1799 by the occupying French army. Two years later, the artifact was captured by the British, who sent it to England the following year. It is currently housed in the British Museum. “Egypt never had a say in the matter,” Hawass said.

In the Louvre in Paris since 1922, the Dendera Zodiac was initially seized by the French in the 1820s. It was “ripped from its position in the ceiling of a chapel in the Temple of Dendera,” according to the petition.

Hawass noted in the petition that there is a distinction between legitimately acquired artifacts and looted ones. The Luxor Obelisk in the center of the Place de la Concorde in Paris, for example, was a gift from Ottoman Egypt ruler Muhammad Ali Pasha in 1830, according to French Egyptologist Luc Gabolde in the Journal of the Louvre.

Egypt is not the only country calling for the return of artifacts, wrote Nicole Daniels of The New York Times. She cites former Dutch colonies, such as Indonesia, Suriname and several Caribbean nations. In the United States, indigenous people use legal routes known as “restorative justice” to reclaim stolen objects. A Congolese activist took matters into his own hands in October 2020 by removing a 19th-century wooden post from a display in the Quai Branly Museum in Paris, which houses artifacts from former French colonies.

Hawass described the repatriation of iconic Egyptian artifacts as a “first step toward the decolonization of foreign museums.” In his petition, he said, “It seems absurd that the British Museum would continue to hold on to such a blatant symbol of its colonial past.”

Foreign profits

Along with the cultural aspect of artifact repatriation, there is an economic side. Egypt’s tourism sector has missed out on several decades of revenue generated by visitors who wanted to see the Rosetta Stone and Dendera Zodiac, which is still on display in the UK.

Before the pandemic limited travel and tourism, the Louvre drew 9.6 million visitors in 2019 and 10.2 million in 2018, “an unprecedented figure for an international museum,” according to management. In its 2018/2019 annual review, the British Museum reported it had 6 million visitors, for a total of 350 million since it opened in 1759.

A 2018 CAPMAS report estimated the total number of visitors (local and foreign) to all 72 museums in Egypt in 2016 was 9.6 million. The 24 museums in Cairo were visited by a total of 5 million, followed by the nine Giza museums, which drew 3.4 million.

The CAPMAS 2018 report estimated total revenues of archaeological, historical, and regional museums totaled EGP 169 million ($6.8 million), a 70% increase over the EGP 99 million in 2017.

It might be impossible to determine the extent to which the Rosetta Stone or Dendera Zodiac contribute to the visitors and profits of the British Museum and Louvre. However, experts speculate the desire to retain these artifacts has a financial motive. “It’s about money, maintaining relevance and a fear that in returning certain items, people will stop coming,” said Nigel Hetherington, an archaeologist and CEO of the online academic forum Past Preservers.

With the opening of the GEM, these two iconic artifacts might increase visitors and revenue. The GEM can house more than 100,000 artifacts. They are from the Pharaonic, Greek, and Roman eras, with the complete tomb collection of the boy king Tutankhamun as the star attraction. Worth $1 billion, it will be the largest museum dedicated to one civilization. National Geographic’s Tom Muller described it as a “museum fit for a pharaoh.” The Ministry of Tourism estimated the GEM would draw over 5 million visitors annually.

Coming home?

The path to repatriation had been in the process for several years now. Since the 1970s, UNESCO has tightened guidelines on what artifacts museums can accept. “If an artifact doesn’t have a spotless history, a museum won’t touch it,” wrote Forbes contributor and archaeologist Kristina Killgrove. In other words, artifacts have to have been legitimately acquired with the paper trail to prove it. In 2007, the UN introduced Article 11 of its Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples.

There have been several successful repatriations of artifacts. In January, AP reported that Egypt received an ancient wooden sarcophagus on display at the Houston Museum of Natural Sciences. Mostafa Waziri, the head of the Supreme Council of Antiquities, said it dates to ancient Egypt’s Late Dynastic Period. It spans the last Pharaonic rulers from 664 BC until Alexander the Great’s campaign in 332 BC.

In September, the US sent Egypt 16 stolen artifacts valued at over $4 million, according to Alvin L. Bragg Jr., Manhattan District Attorney, during the repatriation ceremony. The returned items included a painted coffin, a limestone plaque with hieroglyphic engravings, five illustrative linen fragments that allude to biblical beliefs, a bronze statue of a famed ancient Egyptian musician known as Kemes, and a Roman-era portrait of a lady in Fayoum. “These are priceless pieces of history and culture,” said Bragg during the repatriation ceremony. “They were seized [after] a wide-ranging investigation into illegal traffickers and looters.”

In June 2022, five other looted ancient Egyptian artifacts worth $3 million were found in the museum and returned to Egypt. According to an Ahram report, “the artifacts include a group of painted linen fragments that date … to between 250 and 450 BC depicting a scene from the Book of Exodus.”

Earlier in 2019, a 2,100-year-old golden coffin of a priest called Nedjemankh, looted during the 2011 Revolution, was recovered from the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City. “Thus far, our investigation has determined that this coffin is just one of hundreds of antiquities stolen by the same multinational trafficking ring,” Manhattan District Attorney Cyrus Vance said during the repatriation ceremony. Also that year, Egypt recovered a looted artifact on auction in the UK. It was a cartouche of King Amenhotep I.

There is hope that Egypt could recover many of its most prominent artifacts as country leaders have publicly denounced the looting of artifacts from one nation to benefit another. In a striking address in Burkina Faso in 2017, French President Emmanuel Macron said he “cannot accept that a large part of cultural heritage from several African countries is in France … Within five years, I want the conditions to exist for temporary or permanent returns of African heritage to Africa.” Shortly after this address, Elysée Palace made the poetic clarification that “African heritage can no longer be the prisoner of European museums.”

For Egypt, the crowning achievement would be the repatriation of the Rosetta Stone and Dendera Zodiac. Those are likely the two most important and famous artifacts symbolizing Egypt’s history. “The Rosetta Stone is the icon of Egyptian identity,” said Hawass.