One of the hallmarks of the global economic system since World War II is that cross-border trade gets easier with time. “Global trade, in many ways, makes the world go round,” said a January note from the World Bank. “Think of any electronic good, clothing item or perhaps a chocolate bar; all everyday items which are in consumers’ hands and homes [are] because of global trade.”

That openness created “better jobs, reduced poverty and increased economic opportunities,” said Mona Haddad, global director for trade, investment and competitiveness at the World Bank Group in January. International trade “has lifted more than one billion out of poverty since 1990.”

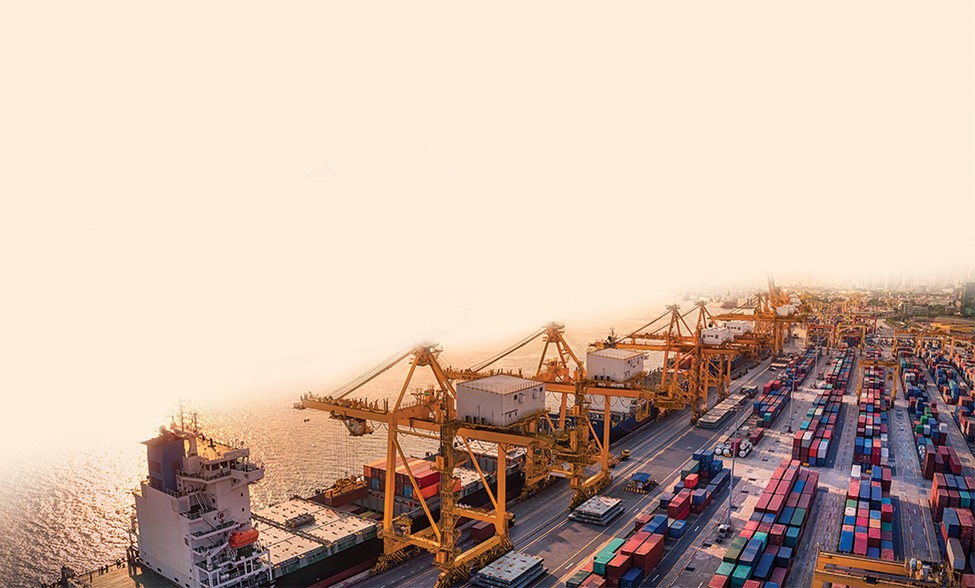

However, the ongoing geopolitical tensions between the United States and China since 2015, the COVID-19 pandemic, and sanctions against Russia since its invasion of Ukraine are changing the global trade landscape. Meanwhile, economic recovery in wealthy nations adds new demands on low- and middle-income exporting countries to rethink their trade and logistics infrastructure.

Trade history

In the 1990s, cross-border trade reached its peak. An IMF paper in June labeled that period an era of “hyperglobalization.” Its main characteristic was that “trade with (at the time) low-wage countries influenced goods prices and wages in advanced economies, benefiting consumers in these countries and workers in exporting [nations].”

The IMF paper said the upside of that boom was surprisingly low inflation despite quantitative easing and increasing national debt.

In 2015, the backlash against globalization was in the limelight as wealthy nations outsourced manufacturing to less developed, low-cost countries. “The Unequal Effects of Globalization,” a newly published book by Pinelopi Goldberg, Elihu Professor of Economics at Yale University, said, “While the average person in the world was better off at the end of the 2010s, many workers in the advanced economies were feeling left behind, doing worse than their parents.”

That aligned with increasing fears from wealthy governments, particularly the United States, that “competition with China was ‘unfair’ given its use of subsidies as well as restrictions imposed on companies seeking access to its market,” the IMF paper said. “This spurred demands for more confrontational policies toward China, especially because it was no longer a poor developing economy.”

The document also highlighted the role of post-COVID-19 supply chain bottlenecks in 2021 in hampering global trade, as major international suppliers came out of lockdowns at different times. That resulted in many governments calling for localizing industries or increasing trade with surrounding and politically friendly nations.

Since last year, the war in Ukraine has further fragmented global trade, as the wealthiest nations imposed sanctions on Russia. However, Russia’s allies, including China and major trade partners in the developing world, didn’t take any punitive action.

The IMF report said the resulting political fragmentation caused countries to “wonder what would happen if they had to decouple from trade partners of opposing political stances overnight. Policymakers concluded … it would be better to decouple immediately on their own terms.”

That means importers no longer use some low-cost suppliers. “Greater trade barriers lead to higher prices, which mean lower real wages,” the IMF paper said. “Globalization may have contributed to … inequality, but protectionism … will likely make the problem worse.”

What happens next

As the world’s biggest economies (China, the United States and European countries) reduce interest rates as inflation cools, trade patterns could change significantly compared to the past three years.

The World Trade Organization (WTO) said in April, “The relaxation of [COVID-19 measures] is expected to unleash pent-up consumer demand … which could provide a boost to international trade.”

To meet rising demand from the world’s biggest economies, goods and products must move faster from source markets. According to the WTO’s April forecasts, “World merchandise trade volume is projected to grow 1.7% in 2023 before picking up to 3.2% in 2024.” That compares with a 3% drop in 2022.

The report said while those growth figures may indicate a recovery in global trade, the regional breakdown is a mixed bag. “Exports from the Middle East [mainly oil] are generally expected to greatly increase to make up for the shortfalls in supplies of Russian energy products,” noted the WTO. Conversely, “Africa was … expected to export greater quantities than it ultimately did. [Instead,] the … dollar value of the region’s exports … increased sharply (18%) due to higher commodity prices.”

However, the WTO warned, “It is difficult to be confident about these [forecast] figures.” That is because their “estimates [are] more uncertain than usual due to the presence of substantial downside risks, including rising geopolitical tensions, global food insecurity, the possibility of unforeseen fallouts from monetary tightening, risks to financial stability and increasing levels of debt.”

Silver bullet solutions?

Amid those uncertainties, governments need to ensure local companies can quickly meet increasing demand from countries with recovering economies. That means faster supply chains to increase exports, which would require significant investments from already cash-strapped economies, such as Egypt. Miishe Addy, co-founder and CEO of Jetstream Africa, a Ghana-based online platform connecting suppliers with producers, told the World Bank in January, “Supply chains [in the continent] are the slowest in the world.”

Another way to speed up the movement of goods at ports is for governments to remove bureaucratic hurdles and streamline processes. “The trade policy solutions [must] exist, and most of them [must focus on being] quick wins … All of [those solutions should] be done at scale,” said Vicki Chemutai, an economist at World Bank Group.

Another solution to expediting the handling and processing of outbound products is to rely more on automation. “Technology and digitization make trade faster, cheaper, easier and more predictable,” said Alina Antoci, senior trade facilitation specialist at the World Bank Group, in January. “Automation makes things more efficient at borders and ports.”

That transformation would result in more efficiency and lower costs. “Automation can lead to increased productivity and reliability, as well as decreased turnaround time for vessels,” noted Port Strategy, a think tank. “This can result in lower costs for shipping companies and faster, more efficient transportation of goods.”

The challenge with more automation may be finding the political will to reduce dependence on humans at ports. “Taking the human out of some of these processes … reduces corruption and makes access to information equitable and reliable,” stressed Antoci.

Regardless of the solutions, Chemutai stressed that innovative solutions are a prerequisite to expediting processes at ports. “The world of trade is not a simple one, and there are pressing issues to address,” she said, “but innovation … is proving revolutionary [in overcoming] so many [of those pressing issues].”