For industrialized economies seeking long-term prosperity, Africa is indispensable. “Many nations are after Africa’s earth minerals,” said Ivan Eland, a senior fellow with the Independent Institute, a U.S. nonprofit, nonpartisan research organization. In addition, “Africa’s expanding population — which will double by 2050 to account for 25% of the world’s population — [is] a huge market for their export.”

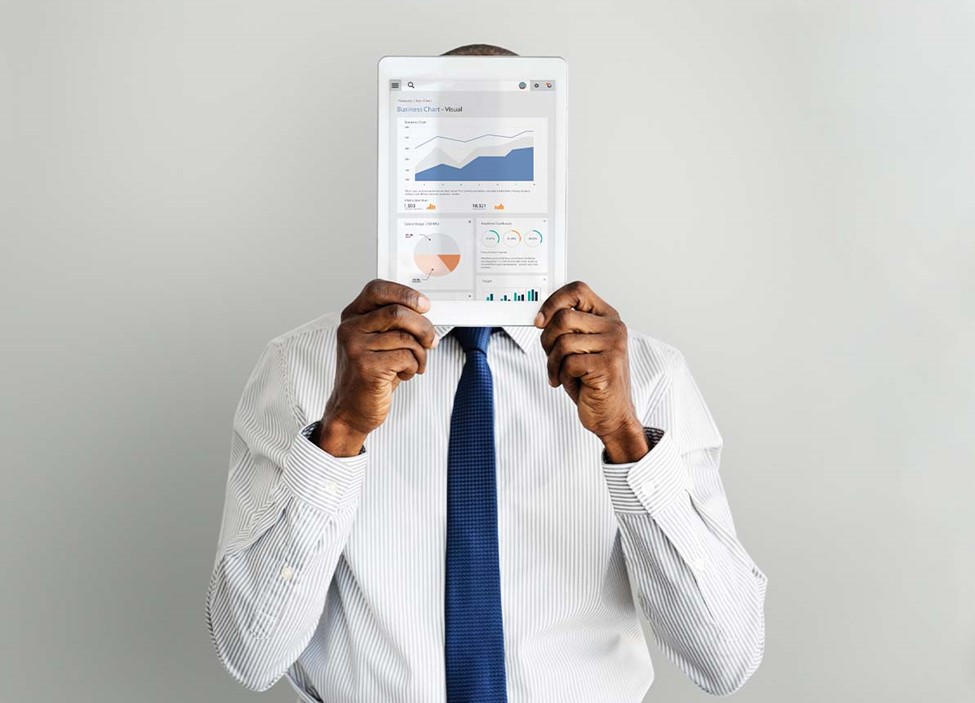

Nonetheless, only a few large economies have invested heavily in the continent. According to data aggregator Statistica, as of October 2021, 51% of Africa’s bilateral trade was with the E.U., China and India. From 2006 to 2016, Russia, Turkey, India and Indonesia increased their bilateral trade relations with Africa by triple-digit percentages, according to the IMF’s 2017 Direction of Trade Statistics report.

At the same time, the United States has distanced itself from the continent. Between 2006 and 2016, Brookings Institution, a U.S. nonprofit public policy organization, said America’s exports to Africa dropped by 66%, while China’s increased 53%. “For decades, the perception of the U.S. has been that it treats African countries like charity cases,” reported Eugene Daniels, White House correspondent for Politico, in March, quoting “several regional experts.” “That was exacerbated during the Trump administration, which largely ignored the continent.”

Throughout 2022, the Biden administration worked to strengthen ties with Africa. “Washington is playing catch-up in Africa,” Cameron Hudson, a senior associate in the Africa program at the Center for Strategic and International Studies, told Politico in March. “With all of the business investment the Chinese have made comes a lot of leverage and political influence in those countries. It’s not just that they’re making money there. They now have skin in the game in Africa in ways that we don’t. And that gives them leverage that we don’t have.”

US in Africa

Despite the decline in bilateral trade figures, the U.S. still commands goodwill throughout the continent. According to Afrobarometer, a nonprofit pan-African research firm based in Ghana, “60% of Africans believe the U.S. has had a positive economic and political influence on their country, just behind China (63%), but far ahead of Russia (35%) and the former colonial powers (46%).”

The positive perception comes thanks to several U.S. government agencies with mandates to benefit African nations. According to a White House briefing document in December, the list includes the U.S. Trade Representative, which has an MoU with the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) Secretariat “to support institutions to accelerate sustainable economic growth.”

There also is the Millennium Challenge Corporation (MCC), which funds 14 African nations to “support regional economic integration, trade, and cross-border collaboration.” A White House briefing said MCC spent $3 billion on active programs, with $2.5 billion in the pipeline.

The United States also invests in the continent via the Digital Transformation with Africa program, U.S. International Development Finance Corporation, Export-Import Bank of the United States, Power Africa initiative, U.S. Trade and Development Agency, Prosper Africa initiative and U.S. Agency for International Development.

The Partnership for Global Infrastructure and Investment provides “timely, coordinated supports [for African] businesses and investors, including micro, small, and medium-sized enterprises, to advance infrastructure priorities and boost two-way trade and investment.”

America has two trade and development agreements with Africa. The first is the Africa Growth and Opportunity Act, a free trade agreement with Sub-Saharan African nations valid until 2025. The second is the Qualified Industrial Zones in Egypt, which exempts products from customs when entering the U.S. if they meet specific criteria.

On the social-support front, the world’s largest economy also has the President’s Malaria Initiative and the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PERAR). The latter has invested $100 billion to combat AIDS globally. According to HIV.gov, a U.S. government portal, “as of Sept. 30, PERAR has supported 30 million … men and boys with HIV infection … in East and Southern Africa.”

Promises

Africa requires significantly more investment to meet its population’s economic, social, development, and environmental needs. According to the African Development Bank, the continent needs at least $10 billion per year for infrastructure plus an additional $50 billion for climate adaptation.

According to the 2021 White House briefing paper, the Biden administration budgeted $1 billion to increase “trade, investment and economic development in Africa.” That has helped the U.S. government “close more than 800 two-way trade and investment deals across 47 African countries.” The value of those transactions was “more than $18 billion.” During that period, the U.S. private sector “closed investment deals in Africa valued at $8.6 billion.” Meanwhile, trade value in goods and services reached $83.6 billion.

The U.S. also is looking to help Africa reduce its carbon footprint. During the November U.N. Conference of the Parties (COP27) meeting in Egypt, U.S. President Joe Biden promised to give African nations “$150 million in an effort to support adaptation efforts … a down payment on the commitment to provide $3 billion to global adaptation efforts for 2024.”

In December, the Biden administration invited representatives from 49 of the 55 African nations and the African Union (A.U.), civil society and the private sector to attend a three-day U.S.-Africa Leaders Summit. The first summit was in 2014.

During last year’s event, Biden’s message to attendees was clear: “When Africa succeeds, the United States succeeds; quite frankly, the whole world succeeds as well,” he said.

That translated to the U.S. government pledging to spend $55 billion in Africa over three years. National Security Adviser Jake Sullivan told the media funding would support “a wide range of sectors to tackle the challenge of our time. These commitments build on the United States’ longstanding leadership and partnership in development, economic growth, health, and security in Africa.”

At the event’s conclusion, the Biden-Harris Administration announced they allocate $15 billion via the U.S.-Africa Business Forum for “two-way trade and investment commitments, deals and partnerships that advance key priorities,” according to the December White House briefing. Priorities include sustainable energy, health systems, agribusiness, digitization, infrastructure and finance.

He stressed that such support would not be conditional on supporting the U.S. position on Russia or China.

Also on the summit’s final day, Biden promised more visits from U.S. government officials. “We’re all going to be seeing you,” he said, “and you’re going to see a lot of us.”

Five top U.S. government officials visited Africa in the first three months of 2023 to discuss cooperation: U.N. Ambassador Linda Thomas-Greenfield and Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen in January; first lady Jill Biden in February; and Secretary of State Antony Blinken and Vice President Kamala Harris in March.

Different narrative

Zainab Usman, a senior fellow and director of the Africa Program at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, noted the current U.S. administration is “breaking from the status quo.” However, it is not all positive, as there have been “some perplexing stumbles.”

The first positive is that “framing the strategy as a ‘U.S.-African partnership’ is a new language.” She also noted the “emphasis on ‘listening’ and the African agency.”

Usman also highlighted America’s commitment to “working more closely with … the [African Union] to address lingering challenges,” citing “the conflict in Ethiopia, especially as it relates to sanctions and suspension of trade privileges under the AGOA [African Growth and Opportunity Act] agreement.”

The other change is the U.S. acknowledgment that Africa is responsible for a fraction of global emissions (3.8%, according to CDP, a U.S. think tank). The language used shows a commitment “to balance climate and development goals by promising to work closely with African countries to determine how best to meet their specific energy needs through various technologies,” Usman said.

U.S. officials stressed that African countries wouldn’t be forced to reduce their respective economies’ carbon footprint if it hurts GDP growth or development efforts. Usman said that based on the new narrative, the U.S. could, for example, finance fossil fuel projects in Nigeria, Tanzania and Mozambique after the World Bank halted funding for those projects at the behest of the bank’s European shareholders.

The hopeful sign is the U.S. administration promising “economic partnerships in areas that speak to both African economic priorities and U.S. strengths,” said Usman. On the ground, the focus would likely be “deploying American financial power to strengthen supply chains for critical minerals such as cobalt, nickel and lithium, and to build core capacities of health systems to manufacture and deliver vaccines and other treatments.”

Lastly, during the December U.S.-Africa Leaders Summit, the U.S. Department of State didn’t mention “security and combating terrorism to address the root causes of instability and violence” on the continent, noted Marwan Bishara, a senior political analyst at Al Jazeera, Qatar’s state media outlet. Instead, the talk focused on “fostering economic engagement, promoting food security, and promoting education and youth leadership.”

However, Usman points to concerns over language that continues to distinguish North Africa and Sub-Saharan Africa. “It is surprising that a strategy that emphasizes its newness continues … dividing the 55 nation-states of the African continent into two groups.”

She explains that AfCTA “parallels [the] European Union, [whose] members all identify as European and in a single trading bloc, despite their sociocultural, linguistic and economic differences.”

Walk the talk

One of the biggest challenges facing the Biden administration in Africa is geopolitical shifts caused by Russia and China. Bishara of Al Jazeera said the lack of U.S. support for Africa led to “when voting on a draft resolution to freeze Russia’s membership in the U.N. Human Rights Council, only 10 of 54 African nations voted in favor, nine voted against and the rest either abstained or did not show up for the vote. South Africa, among America’s leading partners on the continent, championed the abstention drive.”

Usman of the Carnegie Endowment believes the Biden administration needs to implement its promises quickly. “African countries, U.S. allies and development partners, and other stakeholders will be on the lookout for how this vision will be implemented,” she noted. “Achieving intergovernmental coherence among initiatives such as Prosper Africa and Power Africa across the U.S. government will be a crucial indicator of success.”

Politics will play a significant role in the future of America’s involvement in Africa. Usman noted Democrats and Republicans in Congress will determine “how much funding the Biden administration [could] allocate to the [African] strategy’s implementation.” And with a presidential election looming in 2024, a new U.S. leader could reverse those pledges.

The long-term solution to ensure the U.S. increases its presence in Africa is to convince its private sector to venture into the continent. “They don’t see African countries as investment opportunities,” Amaka Anku, head of the Africa practice in the Eurasia Group, a U.S-based consultancy, told Politico in March. “The challenge is not just convincing Africans that Africa’s economic transformation is in the American best interest. It’s also convincing Americans.”