At the beginning of 2021, only a niche group of crypto enthusiasts knew what non-fungible tokens (NFTs) were. But by the end of the year, some $25 billion had been spent on NFTs, compared to $94.9 million in 2020, as the speculative crypto asset exploded in popularity—popular enough to be named word of the year for 2021.

Though NFTs have been around since 2014, the NFT mania hit the mainstream last March when a digital collage of images, titled “Everydays: the First 5000 Days” by digital artist Beeple (aka Mike Winkelmann), was sold as an NFT for $69 million. The historic sale created a ripple effect, and several other NFTs attracted million-dollar buyers, including purchases of Bored Ape Yacht Club and Cryptopunk collectibles.

NFTs are a way to create and certify a digital piece as an original. The tokens are stored on a blockchain, a form of a digital public ledger that records transactions and tracks assets, and are “non-fungible” meaning they can’t be replicated, essentially giving creators proof of ownership. This gives NFT holders value over and above simple ownership—and provides creators with a vector to build a highly engaged community around their brands, says Timmy Mowafi, co-founder of NFTY Arabia, a UAE-based NFT marketplace.

NFTs can be created with anything digital, for example a photograph, a GIF, music and more. The payoff has so far been huge. A video clip of basketball star LeBron James slam dunk sold for over $200,000 and Nyan Cat (a 2011-era GIF of a cat with a pop-tart body) went for $600,000. Musicians Grimes and Kings of Leon generated million dollars from NFTs associated with new album releases. Even tweets count: an NFT of Twitter’s first-ever tweet was auctioned off for $2.9 million.

Morgan Stanley’s November 2021 research note claims that in less than a decade, as much as 10% of the luxury industry will be made up of NFTs traded in the metaverse. “As more aspects of people’s lives move to the internet, demand for digital fashion and luxury goods is set to increase dramatically in the coming years.”

How to Trade NFTs?

With a little technical know-how, anyone can tokenize their work to sell as an NFT. All that’s needed is a digital wallet, a small purchase of cryptocurrency, and a connection to an NFT marketplace where users can upload and turn the content into an NFT or crypto art, a process called “minting.” Some of the portals that cater to NFT purchases are Rarible and OpenSea, which allow people to buy and sell NFTs with crypto- and fiat currencies.

“In theory, you can create the same income in one day of NFT sales that might take you years from monetizing Youtube views, Spotify streams, or garnering enough followers on Instagram to attract freelance gigs,” NFTY Arabia’s Mowafi says, “From a business perspective, launching an NFT project as a startup is an incredible way to raise funds and build a dedicated, sustainable community simultaneously.”

How NFTs are purchased and sold is roughly the same around the world. However, Mowafi explains that Middle East countries “have different regulations for acquiring said cryptocurrency.” In Egypt, for example, crypto trading is illegal under an act that was passed last year and prohibits issuing, trading and promoting crypto locally without explicit licensing from the Central Bank of Egypt’s board. Several other MENA countries have similar bans and restrictions. Some marketplaces, such as the UAE’s BitOasis, enable NFT credit card purchases “via a fiat (a form of aggregator) to the crypto payment processor,” Mowafi explains. These platforms may allow traders from countries like Egypt to enter the NFT market.

The Egyptian Experience

Given how much potential profit is on the table, the popularity of NFTs has unleashed a flood of new ventures in Egypt, with creators taking advantage of their possibilities in different ways.

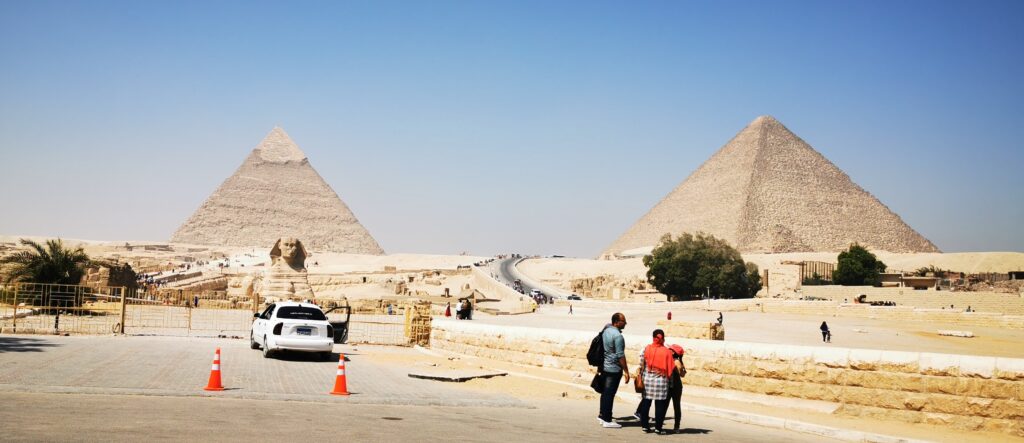

Last October’s contemporary art show at the Giza Pyramids, organized by Art D’Égypte, featured the work of French artist JR, who later issued a multi-layered collection called Greetings from Egypt, comprising 4,591 NFTs.

Similarly, blockchain game developer Enjin piled in with plans to develop NFT versions of Egyptian monuments, including the Giza Pyramids and Great Sphinx, viewable in 3D via virtual and augmented reality technology.

Most recently, Egyptian visual artist Aya Tarek launched Egypt’s first art exhibition curated for an NFT marketplace. Dubbed “Token,” the show merged physical paintings and digital NFT artwork, with digital artworks sold at around $10,000 a piece. Tarek calls the event “an unprecedented success” for her, and noted the bulk of sales were to accounts outside of Egypt. “This is because smart wallets of local users are mostly registered overseas,” she explains, attributing that to Egypt’s government uncertainty regarding cryptocurrency and NFTs.

The CBE renewed last March its warning against the dangers of cryptocurrencies, calling them “extremely volatile” investments that are neither based on tangible assets nor centrally regulated, making them susceptible to sudden losses in value. That said, Egypt has not explicitly banned NFTs, leaving the door open for future business plans to be tied to the concept.

NFTs, Tarek believes, are set to steadily grow in Egypt “with the potential to change the entire landscape of fine art collecting.”