After more than two years of global shocks, Egypt’s external debt continues to mount. As the government tries to rein in a rising debt-to-GDP ratio, analysts say the country needs to focus on FDI and other sources of foreign currency to cover budget gaps and meet its obligations.

Long before the pandemic, Egypt had tapped international financiers to support its economic reform program launched in 2016. But the pace of borrowing has accelerated since March 2020 to fund COVID-19 stimulus programs and more recently to cover the rising prices of wheat, oil and other strategic imports.

In June, Minister of Finance Mohamed Maait told members of the American Chamber of Commerce in Egypt that Egypt’s external debt has been affected by the COVID-19 pandemic, the impacts of the war in Ukraine, and soaring inflation. “All these challenges are pushing the government towards increasing investments and securing more loans to meet its rising financial needs.”

According to the Central Bank of Egypt’s (CBE) latest data, Egypt’s external debt stood at $145.5 billion at the end of Q2 2021/2022, its highest level in two years.

The World Bank in July reported that Egypt’s external debt rose to $157.8 billion in Q3 2021/2022, up 8.4% from the previous quarter. The World Bank calculated Egypt’s debt-to-GDP ratio at 92% at the end of FY 2021/2022.

Egypt is just one of many emerging economies currently struggling with debt. In Bloomberg’s list of countries at risk of defaulting on sovereign debt, Egypt ranked fifth, after El Salvador, Ghana, Tunisia and Pakistan. Sri Lanka defaulted in May, while Russia effectively defaulted on a dollar-denominated loan in June.

Since March 2020, the government has been working with the International Monetary Fund (IMF) on two strategies aimed at reining in the elevated debt.

One of them is a medium-term debt management strategy to decrease Egypt’s debt-to-GDP ratio incrementally to reach 75% by 2027, according to the finance minister. The strategy focuses on moving away from short-term debt, extending the average life of debt stock and expanding the investor base to inject new liquidity to support the country’s budget.

To minimize budget gaps, the government also has a medium-term strategy to increase revenues by 2% of GDP over four years. The plan will support targeted surpluses and priority spending on health, education and social protection.

Looking beyond loans

Egypt recently concluded talks with the IMF to borrow another $6-10 billion, depending on the country’s quota in the IMF’s Special Drawing Rights. This would be the fourth IMF facility since 2016 and the third since the onset of the pandemic.

Speaking to Business Monthly, Hany Abou-El-Fotouh, CEO of Alraya Consulting, noted that foreign currency reserves are expected to drop unless Egypt obtains fresh loans, especially in light of the exodus of local debt investments from the bourse.

Speaking to Business Monthly, Hany Abou-El-Fotouh, CEO of Alraya Consulting, noted that foreign currency reserves are expected to drop unless Egypt obtains fresh loans, especially in light of the exodus of local debt investments from the bourse.

In May, Prime Minister Mostafa Madbouly announced that about $20 billion have fled the Egyptian market since the beginning of 2022. The CBE subsequently reported that Egypt’s net international reserves had dropped to $33.4 billion by the end of June, down from around $41 billion over the past four months.

Securing new loans, however, could become more challenging. Moody’s downgraded Egypt’s credit rating outlook in May from stable to negative, citing the implications of the war on the country’s budget and financial needs.

“The situation of Egypt’s debt is a matter of concern, especially that the current fiscal year will see the country repay a portion of its debt, along with foreign currency shortages and uncertainty about the Russian war in Ukraine,” Abou-El-Fotouh said.

Abou-El-Fotouh urged the government to promote the country as an investment-friendly destination by identifying attractive opportunities for GCC and other foreign investors. Since the onset of the Ukraine war, Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates and Qatar have pledged over $20 billion to support the Egyptian economy.

Ahmed Shawki, a consulting member of the Egyptian Centre of Economic and Strategic Studies, told Business Monthly that expanding foreign direct investment (FDI) is the best way for Egypt to cope with the appreciation of the U.S. dollar and shore up its reserves. “FDI, unlike debt instruments, has a focus on investing in fixed assets, and that is a long-term investment that Egypt needs at the present challenging time,” he said. Shawki named the industrial and agricultural sectors as targets for greater investment.

Shawki listed a number of measures to address Egypt’s rising debt levels. First, the government needs to fast-track its issuances of sovereign sukuk (asset-based bonds compliant with Islamic law) to tap the GCC’s significant appetite for the Egyptian market.

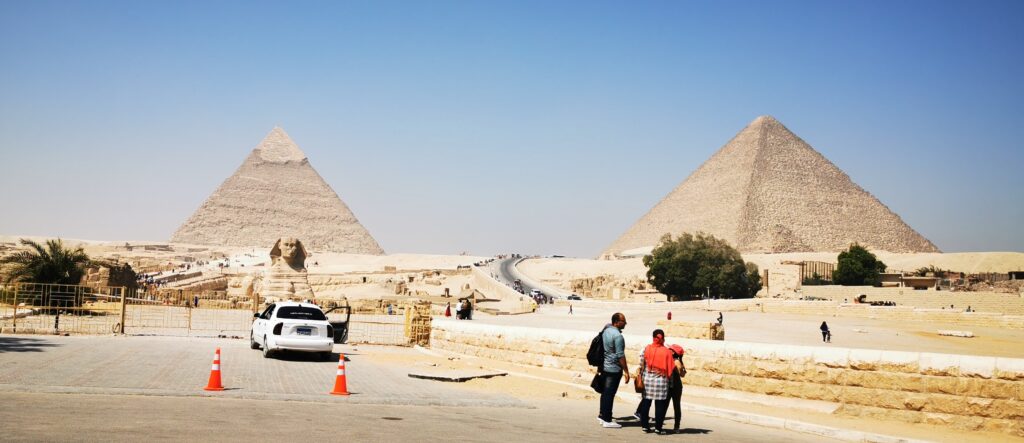

To draw in foreign currency, Shawki said, Egypt needs to quickly capitalize on the increased natural gas demand from Europe. He also called for raising Suez Canal fees to keep up with the global oil price hikes. The tourism sector also needs a push from the government to boost the country’s revenues.

There are no quick fixes, however. With the coronavirus and Ukraine war continuing to disrupt the global economy, Egypt—like other developing countries—will have to make sure its borrowing doesn’t overburden its economy.