This article first appeared in March’s print edition of Business Monthly.

The 2024 U.S. elections could be a watershed moment for America, its allies and rivals, and countries that want to retain a balanced relationship between East and West. “The president chosen in 2024 will … be in charge in the moment of maximum danger,” John Prideaux, U.S. editor for The Economist, wrote in the World Ahead issue published in November.

MENA is one region whose economic policies will likely change in response to the next U.S. president’s actions. It is already strengthening economic ties with nations that don’t see eye-to-eye with America and its allies.

That was most evident with the addition of four MENA countries to the BRICS coalition, comprising Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa, as of 2024. Meanwhile, the increasing number of agreements involving MENA nations to use local currencies in bilateral trade indicates a gradual aversion to the dollar.

Understanding what the sitting president’s and his Republican challenger’s foreign economic policies might be in the coming four years is vital. “Lingering uncertainty about the course of U.S. economic policy could have an appreciably negative effect on global growth prospects,” the World Bank said in a 2017 report. “While the United States plays a critical role in the world economy, activity in the rest of the world is also important for the United States.”

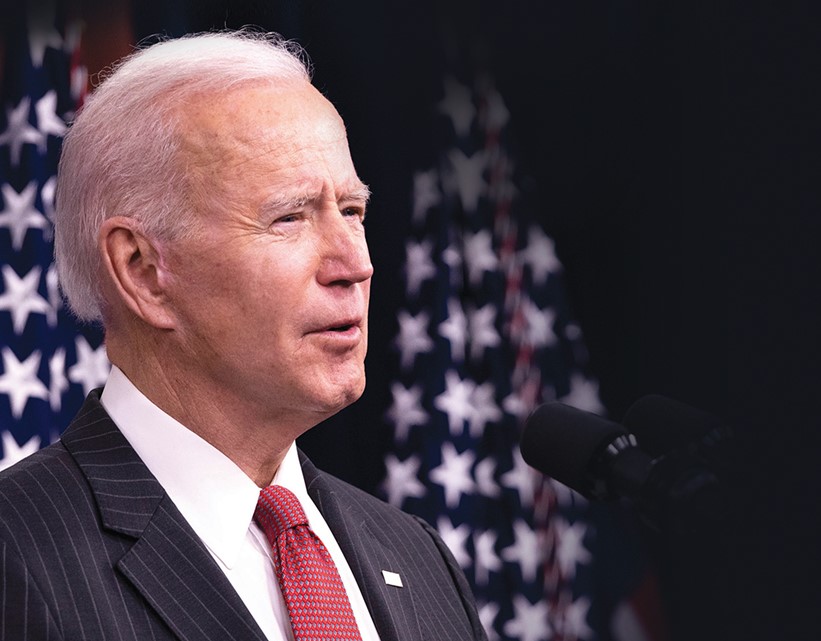

Sitting president

Chris Megerian, AP’s White House reporter, said, “President Joe Biden has a simple re-election pitch to voters — let him ‘finish the job.'” That likely means a second-term agenda that could look like the first one. “We’re going to finish as much of the job as we can in the next year,” Bruce Reed, Biden’s deputy chief of staff, told the media in November. “And finish the rest after that.

From the beginning of his 2020 campaign, Biden’s foreign economic policy changed “the administration’s approach to the world economy,” Dani Rodrik, professor of International Political Economy at Harvard’s Kennedy School, wrote in Project Syndicate in May.

Biden is “pursuing ambitious industrial policies to revive domestic manufacturing and facilitate the green transition. [He] has also adopted a tougher stance on China … treating the Chinese regime as an adversary and imposing export and investment controls on critical technologies.”

Rodrik added the current administration has moved the U.S. “away from traditional trade deals focusing on market access [to] embracing new international economic partnerships that address global challenges such as climate change, digital security, job creation, and corporate tax competition.”

He noted that Biden’s strategy aims to “generate trillions of dollars in investments in emerging economies and provide aid to countries facing debt distress.”

Promoting projects related to climate actions at home and abroad is a top priority for Biden. “Since day one … the entire Biden-Harris Administration has treated climate change as the existential threat of our time,” according to a December White House Fact Sheet.

At the 28th Conference of the Parties (COP28) that closed in December in Dubai, the United States said it pledged $3 billion to the UN Green Climate Fund to finance eco-friendly projects worldwide. Additionally, the Biden Administration said it would “scale up U.S. support for … developing countries” beyond the $2.2 billion offered in fiscal year 2022 as part of the President’s Emergency Plan for Adaptation and Resilience initiative, announced in 2022.

Biden also plans to create new funds to tackle climate impact in emerging regions and support community-based measures to “catalyze technical assistance for vulnerable countries.” There will also be country-specific new funds, such as Resilient Ghana and the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) New Climate Economy “country packages … with government, philanthropic, and private sector partners,” the White House Fact Sheet said.

The Clean Energy Supply Chain Collaborative (CESCC), announced in December, will push suppliers of any U.S.-based company to lower their emissions. CESCC’s blurb said it aligns “like-minded countries to advance policies, incentives, standards and investments to create high-quality, secure, and diversified clean energy supply chains.” The program focuses on foreign companies that want to work with the United States in “wind, solar, batteries, electroliers, heat pumps, direct air capture and sustainable aviation fuels.”

The Biden Administration said CESCC’s budget is “$568 million in new concessional lending [to] developing countries … available from the U.S. Department of Treasury through the Clean Technology Fund.”

The December White House Fact Sheet also noted the current administration’s plans to “jump-start small modular [nuclear] reactor deployments around the world.” It is part of Biden’s plans for the United States and “over 20 countries from four continents” to triple their nuclear energy output from 2020 to 2050.

Lastly, the Biden Administration is working with Egypt in the Net Zero World, created in 2021 at COP26, to “formulate national net-zero policies and roadmaps.”

In 2024, the Biden Administration will be working to increase their “international public climate finance to over $9.5 billion in FY 2023 … to over $11 billion per year by 2024.”

Consecutive-term risks?

One risk facing such plans is that U.S. presidents in their second consecutive terms are often noticeably more complacent than in their first four years. “The additional four years have proven the downfall of many a good president,” said Jonathan Turley, an American attorney and contributor to The Hill. “Some second-term presidents become far too comfortable.”

“A second term for Biden could easily repeat these common failings,” he said, “particularly if the U.S. House remains in Republican hands.” Alternatively, Biden could become “more ideologically aggressive, since [second terms] free presidents from the need to face voters again. Second terms are when presidents are most likely to yield to temptation.”

Regardless of Biden’s approach, if he wins a second term, his decisions will be much faster: “Second-term presidents tend to have little patience for negotiations as they watch their final years in politics ticking away,” said Turley. “If one or both houses of Congress remain under Republican control, Biden is likely to dramatically increase his … use of unilateral action.”

Challenger: Second act

Even though the Republican Party has yet to choose its nominee to challenge Biden in 2024, few are betting against the 2016 winner: Donald Trump. “Barring unforeseen illness or death, the 2024 presidential election will be a rematch between Joe Biden and Donald Trump,” The Economist said in November.

If Trump retakes office in 2024, he will make decisions much faster. “Because … Republicans have been planning his second term for months, Trump 2 would be more organized than Trump 1,” The Economist reported in November.

Trump will likely adopt the same foreign economic policies from his first tenure as president. “In the White House, Donald Trump put more new tariffs on American imports than any president in nearly a century,” The Economist reported in October. “His philosophy was simple: ‘I am a Tariff Man. When people or countries come in to raid the great wealth of our nation, I want them to pay for the privilege of doing so.'”

That has led to fallouts with many foreign companies, as they saw their products becoming more expensive in the United States, making them less competitive. China was particularly aggrieved as the United States is its top export market, and tariffs on its goods went from 3% to 19% under Trump.

A research paper from Chad Bown, an economist at the Peterson Institute for International Economics, a think tank, noted, “By 2021, [when Trump left office], American duties were worth 3% of the country’s total import bill value, double the level when Trump took office.”

Protectionism would likely get more extreme under Trump 2. “He is mulling an across-the-border levy of perhaps 10% on all products entering America,” according to The Economist. Critics speaking to Reuters in November said the policy aims to reduce the U.S. trade deficit but would also raise prices.

In November, AP News reported Trump could “urge Congress [to] pass a ‘Trump Reciprocal Trade Act,’ giving the president authority to impose a reciprocal tariff on any country that imposes one on the U.S.”

If Trump could implement his protectionist agenda, the Federal Reserve would likely increase interest rates to curb inflation from domestic manufacturing revving up to meet rising domestic demand. Prices would also increase if U.S. manufacturers couldn’t cope with demand, as imported finished, intermediate or raw goods would become more expensive because of tariffs.

That would have repercussions on the global economy. “The Fed’s aggressive rate increases last year … stressed the global financial system as the U.S. dollar soared,” said Reuters reporter Howard Schneider in August. It requires “monetary authorities [to increase rates] to prevent widespread dollar funding problems for companies and offset the impact of weakening [local] currencies.”

For Trump to impose such protectionist policies, Schneider said he would have to bring the independent Federal Trade Commission, which enforces antitrust law and promotes consumer protection, under presidential control. Meanwhile, as Trump attempts to “decimate what he terms a ‘deep state,'” reported Reuters in November, companies seeking to start working in the United States or doing business with American companies may have to contend with a different bureaucratic process geared to protect local manufacturing.

Foreign investors and manufacturers that can enter the United States should enjoy more operational freedoms, as Trump has constantly vowed to reduce federal regulations that “limit job creation.” During his rallies, he spoke of lowering taxes for domestic manufacturers and pressuring the Federal Reserve to lower interest rates, even if inflation is above the Fed’s 2% target. That means cheaper credit, higher consumption and improved GDP growth at the expense of rising prices.

Foreign companies in the United States may also benefit from Trump’s more ambitious plan to build 10 new “freedom cities” on federal land, each roughly the size of Washington, DC. reported CNN in March.

“These freedom cities will reopen the frontier, reignite American imagination, and give hundreds of thousands of young people and other people, all hardworking families, a new shot at home ownership and, in fact, the American dream,” Trump said in a video announcing his candidacy for the 2024 election.

If he wins, Trump’s energy policies would likely contradict Biden’s. For example, the potential Republican nominee is targeting more fossil fuel activity by simplifying approval processes and paperwork for drilling companies and firms that do business with them to operate in the country.

He also noted he would pull the United States out a second time from the Paris Climate Accords, having done so in 2016, which Biden reversed in 2020. Trump “would also roll back the Biden White House’s electric-vehicle mandates and other policies aimed at reducing auto emissions,” Schnieder said.