By 2050, the number of air conditioners (ACs) in use will reach 4.5 billion, up from 1.2 billion in 2022 due to global warming, which accounts for a rise of 0.5-degree Celsius in global temperature by the end of the century.

ACs eat up over 50% of the electricity consumed during the summer months in Egypt, making it a real environmental challenge, according to Alaa Olama, United Nations Environmental Programme (UNEP) consultant and the head of the Egyptian District Cooling Code.

Egypt has been looking for environmentally friendly city-wide cooling options to cool its cities and reduce its carbon footprint, particularly in its new cities such as New Administrative Capital and New Alamein City.

“If you get out of cities in Egypt you find climate-resilient success models – like mud brick houses with wooden ceilings that remain cool in the summer and warm in the winter,” Sarah El Battouty, architect and founder of ECOnsult said. “We need to tap into the climate resilience of indigenous communities and take inspiration from what they have been doing.”

Sustainable cooling systems

Previous research found that building envelopes – the exterior walls, foundations, roof, windows, and doors – are responsible for nearly half of all heat gains in buildings. These heat gains must be expelled via cooling systems, Michael William, building energy analyst and professor at Coventry University in Egypt, said.

In May, the UNEP announced that it concluded a feasibility study on a district cooling system called the “seawater AC system” for New Alamein City – located on the North Coast. Cold Mediterranean Sea water is pumped into a cooling station to absorb heat from buildings.

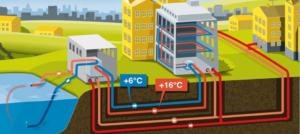

District cooling systems use underground pipes to distribute cooling capacity from a central source to multiple buildings. It is nearly 33% more efficient than ACs – which usually consume around 3 kilowatt hours (kWh) to generate and deliver 1 kWh to the end-user.

According to the study, the project has a single district cooling plant that can be built over two years at a cost of $117 million for the production facilities and an additional $20-25 million for the distribution network.

With this cooling system, the city would reduce refrigerant emissions by 99% and carbon dioxide emissions by 40%. This is especially significant because the cuts will help Egypt adhere to the provisions of the Kigali Amendment to the Montreal Protocol on Substances that Deplete the Ozone Layer for phasing down hydrofluorocarbon (HFC) – compound found in refrigerants including ACs – and its emissions.

The Montreal Protocol is a global agreement signed in 1987 to prohibit the production and distribution of ozone-depleting substances and to reduce their levels in the air to protect the earth’s ozone layer. In 2019, the “Kigali Amendment” was passed to cut projected HFC production and consumption by more than 80% over the next 30 years.

However, Ahmed Abdel Ghani, CEO and chairman of Allied Consultants, an engineering consultant and project management firm, highlighted that the biggest challenge to seawater cooling systems is the high cost. “To be able to operate this system, we will need to build long pipes which will run far and deep in the sea to reach cold water. These pipes are very costly to build.”

Benefits of district cooling

The pressing environmental crisis has driven many hot countries in the region – like Egypt- to consider their energy usage and carbon footprint, especially with energy prices on the rise due to the global energy shock.

Cooling systems like AC units account for more than 7% of global greenhouse gas emissions. Emissions are cut by over 50% using district cooling systems, according to the International Energy Agency.

In areas without electricity, these district systems can be powered by solar or geothermal energy, which reduces energy consumption and CO2 emissions. “If we combine efficient insulating materials and building design, we could achieve 50% energy savings,” William said.

The primary advantages of district cooling systems are lower energy consumption and operating costs, according to Abdel Ghani, when compared to cooling every building individually. While traditional split units may seem cost effective (running as low as EGP7000) to the end user, the government pays EGP50,000 to bear the cost.

In fact, Egypt has built a district cooling plant in the New Administrative Capital. However, it is not applied throughout the city and is restricted to specific districts within the capital, such as the Government District, Abdelghani said. Nevertheless, the city permits other developers to incorporate district cooling into their real estate projects.