Fustat’s new National Museum of Egyptian Civilization is a worthy prelude to the highly anticipated opening of the Grand Egyptian Museum, heralding a new age of tourism.

Billed as the “Pharaohs’ Golden Parade,” the mummies of some of Egypt’s most immortalized rulers emerged from their resting places in a lavish procession through Cairo. The mummies of Ramses the Great, Seti I, Thutmose I and Ahmose Nefertari were among the 18 kings and four queens that made the journey about 3,000 years after their burial in the iconic Valley of the Kings and Valley of the Queens in Egypt’s distant south.

This time, however, their burial chambers in the new National Museum of Egyptian Civilization (NMEC) have been impressively purpose-built to venerate their legacies, further preserve bodily integrity (which the ancients managed with matchless proficiency) and offer the local and international public an opportunity to conveniently, informatively and comfortably view them in all of their glory.

What completes the appeal of the recently inaugurated NMEC, which opened April 18, is the fact that it is not solely a mausoleum to Egypt’s pantheon of pharaonic demigods. Instead, it was conceived and commissioned in collaboration with UNESCO to serve as a comprehensive chronological exposition of the entirety of Egyptian civilization. This characteristic, coupled with the NMEC’s easily navigable size, partitioning and structural arrangement, ensures a rich “in-a-nutshell” viewing experience.

Indeed, the NMEC signifies not only the government’s concerted push to reposition Egypt’s beleaguered tourism industry, but a broader initiative to honor Egypt’s role as custodian of priceless relics from time immemorial.

First impressions

The NMEC is located on the archaeological site of El-Fustat in Old Cairo, overlooking Ain El-Seera Lake. A large esplanade greets visitors styled similarly to ancient Egyptian temples and monuments with large stone slabs, angular subsections, and imposing columns. Visitors end their viewing experience by exiting onto the raised platform overlooking the lake and looming limestone cliffs a short distance across the water. A restaurant here offers a relaxing way to end the museum experience.

The Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities developed NMEC in tandem with the planned revitalization of a historic part of Old Cairo, including El Moez street, another part of the government’s efforts to reinvigorate the capital’s heritage sites for tourists to enjoy more freely and easily than ever before.

We visited the museum as a party of five on the last Tuesday in April and were surprised to see the museum’s entrance hall brimming with masked international and local visitors.

Immediately noticeable is the museum’s appealing yet relatively compact size, constructed in an almost circular shape consisting of two levels. At the heart of the high ceiling in the vast main foyer, an inverted glass pyramid points to the center of a wide portal that looks down onto the chamber of mummies below. From this upper level, you can view an impressive videographic montage of some of the most remarkable examples of ancient Egyptian art projected in high-definition onto the ground below.

As we walked into this grand foyer, we were able to see nearly all of the exhibits on the main level. The museum is arranged chronologically around this circular concept, whereby viewers walk around the center while encountering progressive periods of history: prehistoric, pharaonic, Greco-Roman, Coptic, Islamic, and, finally, modern Egypt. The NMEC’s minimalist, understated architecture maintains a spotlight on the exhibits.

This setup was an appreciated facet of the NMEC, which we all thought gave an added element of uniqueness. We also felt this was essential to its complementary role with the original Egyptian Museum in Tahrir Square and soon-to-open Grand Egyptian Museum.

Other welcome features are adequate signage, placards, and text identifying and explaining nearly every artifact. At the Egyptian Museum in downtown Cairo, many informational placards are outdated, missing, or inadequate.

The NMEC, although clean and well-lit, could benefit from more natural light. However, this might have been intentional to emphasize artificial white light, which arguably offers more clarity. Nearly all exhibit sections allow for a 360-degree viewing experience, and many more oversized items were displayed prominently and not encased.

In a nutshell

Perhaps the most standout feature of this museum is its organization around the principle of a chronological journey through the eras of civilization, instead of focusing on the popular pharaonic period.

The curation of the displays gives a complete picture of each period, which is no small task given the amount of time covered and the number of stories to tell. Among the more intriguing items are loaves of bread more than 3,000 years old that look like they might have just come out of an oven.

Also intriguing is the imposing and austere, towering statue in the main viewing hall of the pharaoh Akhenaton, with his characteristic pot belly, elongated skull, and disproportionate features. Akhenaton was known for abandoning Egyptian polytheism for a monotheistic system of worship of the sun deity Aten thousands of years before Constantine converted the polytheistic Roman Empire to Christianity.

Akhenaton’s unembellished depiction stands apart in ancient Egyptian history. Egyptologists maintain that he insisted on his likeness depicted most truthfully, unlike almost all other pharaohs. Next to his statue was a large-scale translation of the “Hymn of Akhenaton,” which, after close reading, stood out to me as one of the most beautiful pieces of poetry I have encountered from the ancient world.

The museum features a myriad of jewelry, pottery, mosaics, garments, ornate furniture, figurines, and all manner of trinkets from the critical eras of Egyptian history. Exhibits range from early Coptic religious garments and monastic doors to the last Egyptian-made kiswah (the ornate covering of the Kaaba) from 1962 and mahmal (the elaborate vessel holding the kiswah on its journey to Mecca) to an alabaster statue of a traditional female water bearer by Egypt’s most acclaimed modern sculptor, Mahmoud Mukhtar (1891-1934).

Into the chambers

After visitors complete the first level and its crash course on the various eras of Egyptian civilization, they enter the chamber of mummies, a dimly lit underground collection of smaller viewing chambers connected by weaving passageways. The transition is a seamless passage down a ramp and through the archways of a mock pharaonic temple facade, leading into the section of the museum dedicated solely to the exhibition of the 22 astoundingly preserved mummies of some of the most extraordinary personalities in the pharaonic lineage.

Viewing rooms for the mummies on display at the NMEC are a marked improvement from the Egyptian Museum, where they were crammed into dank, dusty rooms or encased in glass boxes in need of refurbishment. However, at the NMEC, these mind-blowing examples of ancient Egyptian ingenuity and history receive the treatment they deserve.

All mummies at the NMEC are displayed behind clean, clear glass at 20 to 21 degrees Celsius for optimal preservation, and informative placards accompany each. The mummies are given enough space for the most traffic-free and comfortable viewing experience while adding to the allure of each mummy in the process.

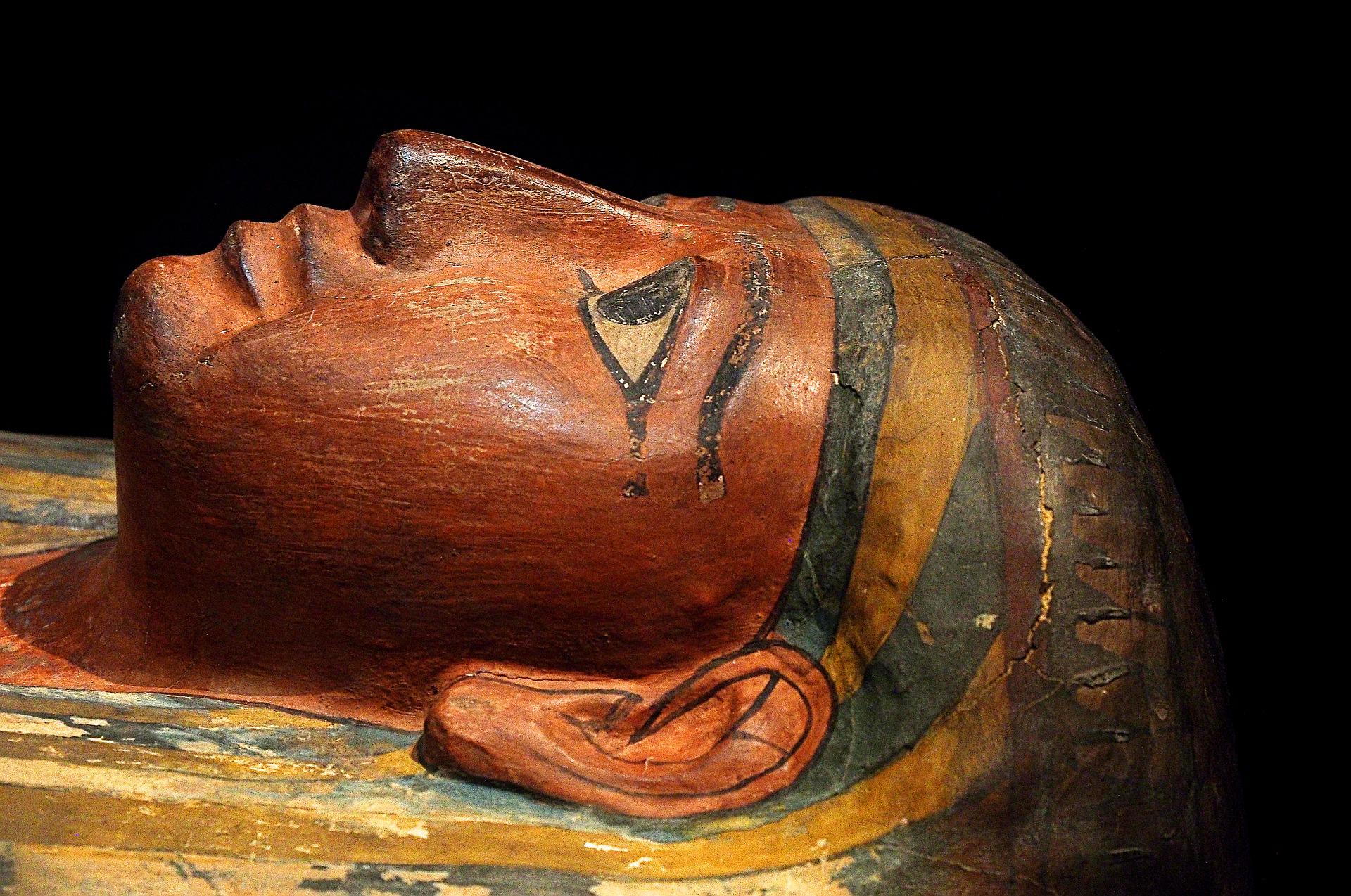

Stepping into the chambers, there is a palpable feeling of the pharaonic concept of the underworld, where souls would be reinvigorated for the afterlife. The sharp chill of the temperature-regulated space only encourages this sensation. Inside these chambers are the most impressive assets of the NMEC, the giant wooden sarcophagi and mummified remains of Egypt’s pharaohs of antiquity. Most striking and unforgettable were the grotesque and dramatic contortions and poses of some of these mummies.

There were disfigured visages, some with vivid expressions of anguish and torment, contrasted with others frozen in the embrace of solemn tranquility. One mummy showed signs of a fatal blow to the head that fractured his skull, as well as several other visible wounds. Despite a gruesome death and the uncompromising passage of time, it remains intact.

The NMEC is the latest addition to a trifecta of museums that will usher in a new era of tourism for Egypt. It certainly stands in its own right as a veritable embodiment of the country’s long and diverse heritage. Admission is EGP 200 ($12.76) for ex-pats and foreigners and EGP 60 for locals. The museum is open 9 a.m. to 5 p.m. daily, with extended hours of 6 p.m. to 9 p.m. on Friday.