The last quarter of 2023 was pivotal for global trade between Europe and Asia, as Yemen’s Houthi rebels began sinking and seizing freight ships entering the Red Sea through its southern strait in response to the escalating violence in the Gaza Strip.

Those attacks had massive repercussions for Egypt’s foreign currency inflow. “Since the onset of attacks in late 2023, major carriers have rerouted hundreds of vessels to avoid the Red Sea, resulting in historically low Suez Canal volumes [one of Egypt’s top five sources of foreign currency at the time],” said Project44, a think tank, in August. “In 2024, container vessel traffic dropped by approximately 75% compared to 2023, and these reduced levels have persisted into 2025.”

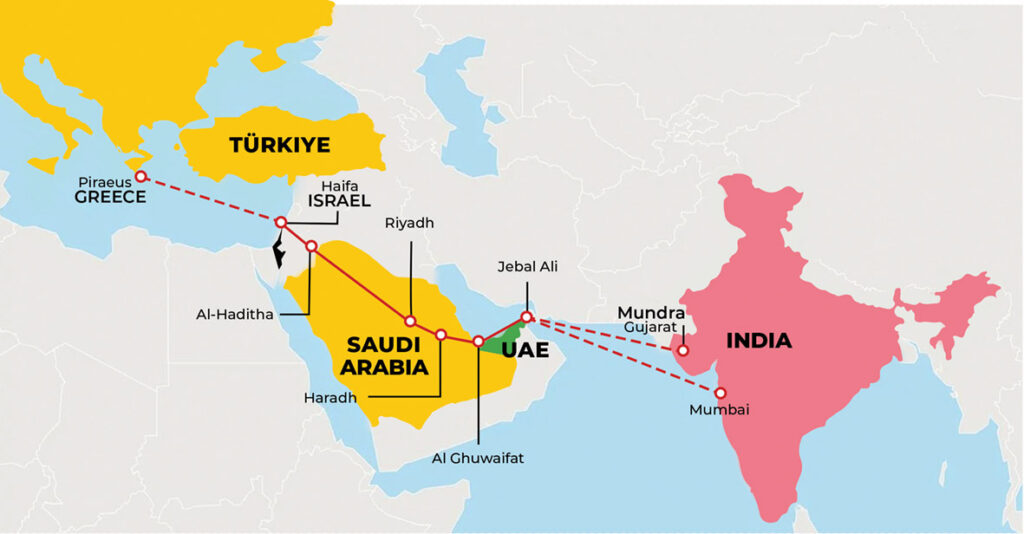

One viable option to replace the Red Sea route is the India-led India-Middle East-Europe Economic Corridor (IMEC), announced in September 2023. Initial plans were to run through Israel and Jordan to reach the Mediterranean. However, with ongoing domestic disruptions, it now looks unfeasible.

In June, Hebatallah Adam, director of the India-based Jindal Centre for the Global South, suggested Egypt as a better alternative to access the Mediterranean. Its strong relations with other IMEC countries and existing trade infrastructure work in its favor.

For now, progress on this route has been slow, with sections operational but not connected. According to Prasanna Karthik, vice president of the Adani Group, “Transportation corridors such as IMEC are fundamentally economic instruments. For the IMEC to succeed, it must first and foremost make economic sense.”

A new route

A March 2025 report from the Research and Information System for Developing Countries (RIS), an India-based research firm, said the IMEC “will not only strengthen economic ties, but also create new opportunities for global supply chain diversification, reducing reliance on traditional trade routes.”

This new route’s importance is increasing. “Amidst economic uncertainty, shifting geopolitics and climate challenges, the IMEC emerges as a resilient, future-ready economic corridor that embodies sustainable and secure trade practices,” noted the RIS.

The IMEC route extends from the ports of Mumbai and Mundra in India to Jebel Ali port in the U.A.E., heading toward Al Ghuwaifat in Saudi Arabia. From there, it could either proceed northwest through Israel and Jordan or southwest to South Sinai. From either destination, the IMEC would head to one of Europe’s southern ports, from which goods could be distributed throughout the EU.

This route features “an integrated network of roads, ports and railways,” noted the RIS report. As it travels on land most of the way, the IMEC could be a “growth corridor,” enabling more cities to connect to it over time.

The IMEC would have several benefits. Aside from bypassing the volatile southern Red Sea strait, the RIS said it would “enhance physical and digital connectivity,” with multimodal transport systems, as well as “energy sector cooperation” since “submarine cables” along the route could “link energy grids and hydrogen pipelines.”

The IMEC also should “pave the way toward a financial corridor, [including] interoperability with existing financial systems.” “Trade connectivity” could enable “global value chain integration, and all tariff and non-tariff issues like technical barriers to trade may be addressed.”

Lastly, the corridor should create education and skills convergence, as “India’s prowess in higher education and technical education might address the needs of several nations in the Middle East, according to the RIS. “Building a skill corridor with these countries would offer possibilities for localization and cross-border flows of goods and services, including skilled manpower.”

To build the route, the RIS said the Partnership for Global Infrastructure and Investment, a G7 funding initiative, should help bridge the infrastructure gap in countries requiring support. Additionally, India’s government “approved the Intergovernmental Framework Agreement, which contains a detailed coordination framework between India and the U.A.E.”

Good for business

An August Atlantic Council report estimated “the corridor would have the capacity to move about 46 trains daily carrying 1.5 million storage containers annually on single-stack cargo rail.”

It also forecasts “transhipment times … reduced by about 40% (to 12-plus days), generating approximately $5.4 billion in annual savings on Asia-Europe trade travelling the route relative to maritime routes.”

Research from the University of Kashmir, published in January, said the “IMEC is expected to boost trade between India and Europe by 40%, reducing logistics costs and speeding up trade in goods and services among the member countries.”

It also would strengthen business relations between India and GCC countries, which accounted for 15% of India’s total in 2024, according to the research paper.

Missing parts

As of August, signatories of the IMEC agreement included India, the U.A.E., Saudi Arabia, Italy, France, Germany, and the United States. Oman, Israel, Jordan, Egypt and Greece have not signed the agreement.

A report from the Atlantic Council in August said the IMEC faces a $5 billion finance gap to become “minimally operational.” That deficit is preventing construction of logistics hubs at several sites, including Haradh and al-Haditha in Saudi Arabia, the report said.

Another complication is that Egypt, Jordan and Israel, the three “last-mile” ports before Europe, are not signatories and haven’t allocated any logistics investments for the IMEC. Without them, the route could not link India to Europe.

“The most active segment of the IMEC has been the connection from India to the U.A.E., which has seen strong investments by both governments,” said the Atlantic Council report. Those projects were possible under the Intergovernmental Framework Agreement, the U.A.E.-India Virtual Trade Corridor and the Master Application for International Trade & Regulatory Interface (MAITRI) that could create a single interoperable and harmonized trade portal.

Saudi Arabia also has seen IMEC-related investments, “particularly port and rail developments associated with the KSA’s Vision 2030 along the Red Sea and strengthening connectivity with India,” the Atlantic Council report said. The most significant Saudi gap is in rail connections to either Egypt or Jordan and Israel, depending on which side signs the IMEC agreement.

There also is uncertainty regarding Oman’s role, which the Atlantic Council report noted “can provide an important auxiliary point of access to the Arabian Sea that bypasses the Strait of Hormuz, a crucial choke point for global energy trade.”

Making it work

The RIS report noted that “while IMEC projects are envisioned to be transboundary, alignment with national policies would be … necessary.” That is because, aside from infrastructure and cross-border connectivity, “success of IMEC projects would also be determined through localization, local capacities and local ownership.”

One alignment pillar the RIS report highlights is “adhering to Quality Infrastructure Investment (QII) principles as endorsed by G20 Japan in 2019.”

To reach an alignment consensus, the RIS report stressed the importance of an IMEC Forum. It would include government officials, public and private financiers/financial institutions, industry experts (infrastructure, construction, transport, and logistics companies), and academic experts (such as think tanks and public policy institutes).

Its goal would be to “establish a roadmap and vision, draw key conclusions from sectoral taskforce studies and assimilate the findings across relevant government and private stakeholders.”

Geopolitical IMEC

According to the August Atlantic Council report, the EU and the UK are strengthening economic relationships with India. In February 2024, France appointed a special envoy to the IMEC. A year later, EU Commission President Ursula von der Leyen committed to “undertake concrete steps for the realization of the IMEC.“ In April, Italy also appointed a special IMEC envoy.

Other EU nations, including Germany, are “slowly building momentum behind IMEC,” the Atlantic Council report said. Germany is supporting multimodal infrastructure, energy projects, and digital investments in Central and Eastern Europe, where IMEC cargoes likely will cross.

The current U.S. administration also supports the IMEC. In February, U.S. President Donald Trump and Indian President Narendra Modi identified the IMEC as a strategic priority, the report said.

The reason for U.S. interest in the IMEC is that it would “promote numerous U.S. foreign policy priorities,” the report said. Those include “reducing opportunities for … adversarial actors, particularly China and Russia [in] Eurasia”’; “deepening bilateral and strategic relationships with India and [the] Gulf” and ““reinforcing the U.S. digital standard-setting approach, with American technology embedded within leading emerging economies like Saudi Arabia and India.”

The Atlantic Council Report also noted the “IMEC [can be] the bedrock for a potential future special economic zone that aligns tariff policy with shared trade standards and supports market entry for U.S. companies in strategic sectors across IMEC countries.

Lastly, the world’s largest economy is betting the IMEC would “strengthen coordination between key U.S. partners in ways that also reinforce the role of the United States as the partner of choice,” the report said.

New global power?

According to the Kashmir University paper, support from Western nations for the IMEC stems from their shared belief that “any geoeconomic advantages made by China in the region will automatically result in a loss for the West” and that the “IMEC will impede China’s geoeconomic ascent in the Middle East.”

A July 2024 report from the EU Institute for Security Studies (EUISS) pointed out the IMEC “emerged … as a potential alternative to China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI).”

However, the Kashmir paper noted that while “it is challenging to forecast the geostrategic ramifications of this multifaceted corridor, it is illogical to believe that it will cause [the Middle East] to turn away from China.”

The research paper explained that Middle Eastern countries “see their relations with the United States and China as a win-win situation,” adding that their policymakers “do not acknowledge that they are faced with the difficult decision of supporting China or the United States in the ongoing economic competition.” Instead, their focus is to “grow their networks in the Global South, the East and the West.”

Ultimately, the IMEC’s success will depend on two main pillars. The first is “building such a vast network that requires overcoming technical, financial, and political hurdles. Regional conflicts, the exclusion of key players and differing priorities create a complex geopolitical landscape,” EUISS said.

The other is that “competition with China’s BRI adds to the uncertainty,” the EUICC paper stated. “The IMEC’s future hinges on navigating these complexities and securing long-term commitment from stakeholders. Realizing IMEC’s full potential will be a long-distance marathon, not a quick sprint.”